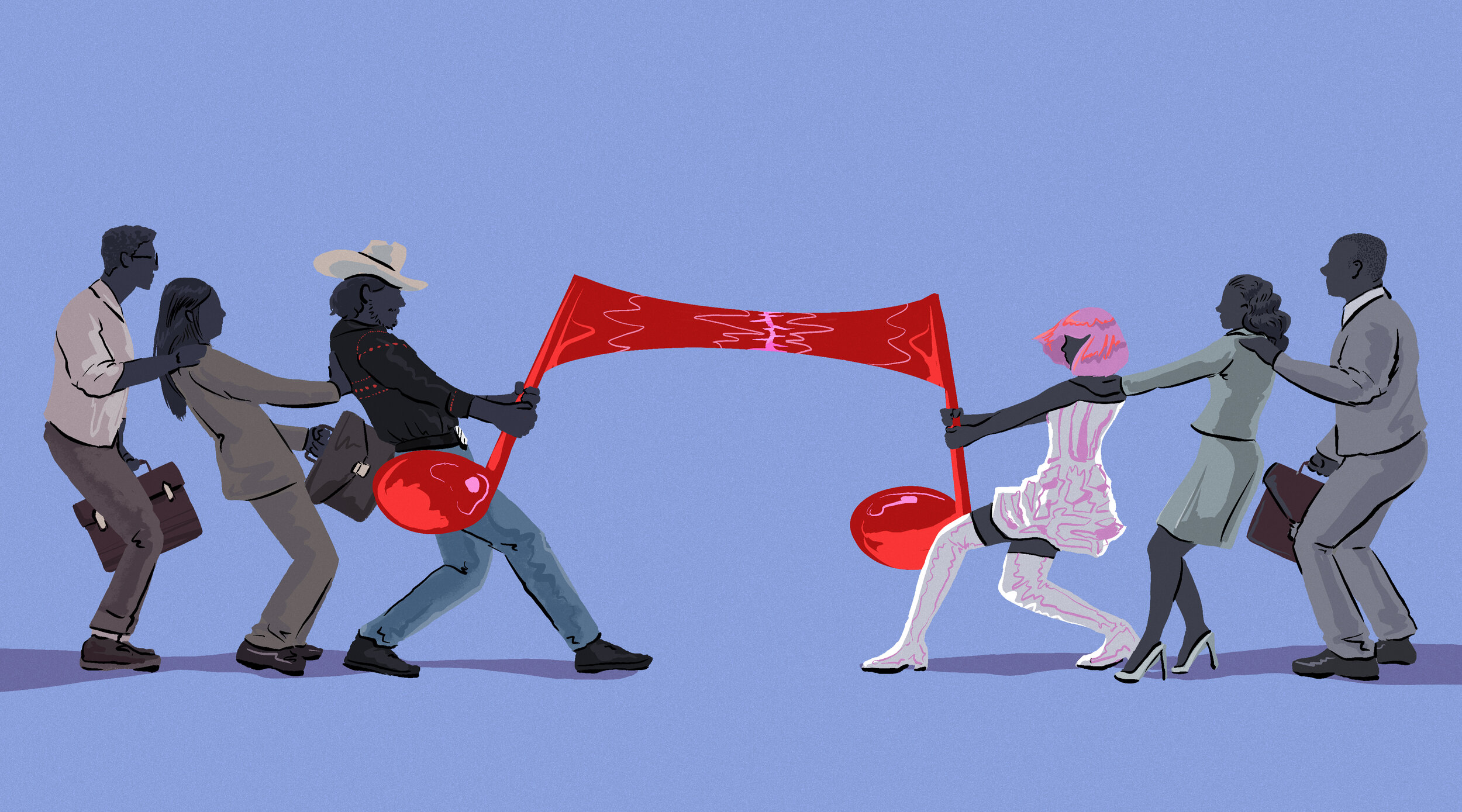

Art by Lauren Davis.

This episode was originally written & produced by James Introcaso.

Broadway’s award-winning, record-breaking, smash hit, Hamilton, is a musical unlike any other. In this special episode, we have re-voiced, remixed, and remastered one of our shows about our favorite broadway musical! Featuring Nevin Steinberg, Hamilton’s Tony-nominated sound designer, Benny Reiner, Grammy-winning Hamilton percussionist, Anna-Lee Craig, Hamilton on Broadway A2, and Broadway sound design legend Abe Jacob.

MUSIC FEATURED IN THIS EPISODE

All music in this episode is from the “Hamilton, An American Musical Original Broadway Cast Recording” soundtrack.

Twenty Thousand Hertz is produced out of the studios of Defacto Sound and hosted by Dallas Taylor.

Follow Dallas on Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and LinkedIn.

Join our community on Reddit and follow us on Facebook.

Become a monthly contributor at 20k.org/donate.

If you know what this week's mystery sound is, tell us at mystery.20k.org.

To get your 20K referral link and earn rewards, visit 20k.org/refer.

Check out SONOS at sonos.com.

Consolidate your credit card debt today and get an additional interest rate discount at lightstream.com/20k.

View Transcript ▶︎

[MUSIC: “Alexander Hamilton Instrumental”]

You’re listening to Twenty Thousand Hertz.

Even if you haven’t seen Broadway’s eleven-Tony-winning, box-office-record-breaking smash hit, Hamilton, odds are... you’ve heard of it. It’s well known for the price - and rarity - of its tickets.

[SFX: News sound bite]

“Tickets for the universally acclaimed musical, Hamilton, are constantly selling out… almost 900 hundred dollars a pop.”

[SFX: Oscar Clip at 02.08.04]

“Lin-Manuel Miranda is here with us. I have to say, it’s weird to see you in a theater without having to pay $10,000.”

[CLIP: Stephen Colbert]

“I went and saw it… and then two hours later I’m going, ‘Why am I crying over Alexander Hamilton?’”

[CLIP: Obama]

“In fact, Hamilton, I’m pretty sure is the only thing that Dick Cheney and I agree on.”

Every element - from the performances to the lighting, to the staging, to the costumes - comes together to create a moving, inspiring, and unconventionally patriotic story that stays with you long after the curtain closes. Each piece of the production is meticulously crafted... and sound design - is no exception.

Abe: There were some moments in Hamilton, which only work so very well because of the subtlety of the sound design and the soundscape.

That’s Abe Jacob, a Broadway sound design legend.

Abe: I've been a sound designer for the last almost 50 years.

Abe is considered the godfather of sound design on Broadway. He worked on the original productions of revolutionary shows like Hair, Jesus Christ Superstar, and Chicago.

Abe trained many of the industry’s working sound designers today, or he trained the people who trained them.

[music out]

Abe: At the time when I started, nobody else was credited or titled sound designer, so I sort of started that industry. That's probably one of the things that I'm most proud of.

When Abe says that Hamilton has remarkable sound design, it’s a huge compliment.

Abe: The sound of Hamilton has got to be very difficult because you're listening to a hip-hop sort of musical style, as well as dialogue, as well as legitimate Broadway show tunes. The combination of all three of those elements coming out with a coherent whole, is a very good example of the talent the sound designer came up with up. There are a number of moments in the show where sound is very subtle, and yet it tends to solidify the whole meaning of the piece.

So, just who is the sound designer of Hamilton?

Nevin: I'm Nevin Steinberg and I'm a Broadway sound designer.

Nevin’s been working on Broadway shows since the 90’s. His work is extensive. He’s been working with Lin-Manuel Miranda on Hamilton from the beginning… and even before that.

[Music clip: “In the Heights”]

Nevin: I worked on a Broadway show called In the Heights which was written by Lin-Manuel Miranda and directed by Tommy Kail. And I was part of a creative team that brought it to Broadway and the show won a Tony award and did very well.

Nevin: When Hamilton was beginning its development, Tommy would occasionally just drop me an email or a phone call with information and kind of a little backstage look at what Lin was working on and what the plans were for this piece. I knew it was gonna be something interesting and exciting to work on, not to mention a lot of fun.

Nevin started his journey with Hamilton where every member of the creative team began - with the script.

Nevin: I'm given the text. And then after I've read it, the first conversation with the director happens. That's the beginning of the sound design for a show.

Nevin: The director and I and representatives from the music department including the composer or the orchestrator, music supervision, we talk about architecture, about the what it looks like and how it moves and then we talk about the venue. Is it a 200 seat venue? Is it a 2,000 seat venue and we start to put ourselves in the position of an audience encountering this story and start to think about how sound can help communicate it.

Nevin: And that process can go on for years, when it does, usually the sound design turns out better.

That’s exactly what happened with Hamilton. Nevin and the rest of the creative team talked about the show for years. He was there when the show was in pre-workshop mode with just a few actors and a piano.

[Music clip: White House Poetry Slam Performance]

Nevin’s job as sound designer is to create the show’s soundscape. He puts the team in place that cares for all of the microphones, on both actors and the orchestra, as well as all of the sound equipment. Nevin balances the volume and sound quality of all of the audio elements in the show to communicate the narrative. He doesn’t just make the show louder, he dictates the story’s dynamic range and makes decisions on how to process the actor’s voices to serve the mission of the story. It’s his team who blows the roof off of the theater with the introduction of this bombastic American spy…

[Music clip: Yorktown]

[“HERCULES MULLIGAN!

A tailor spyin’ on the British government!

I take their measurements, information and then I smuggle it”]

Nevin’s team also sucks the life out of the room when the story gets intimate, to draw the audience in.

[Music clip: Burn]

[“I saved every letter you wrote me

From the moment I read them

I knew you were mine

You said you were mine

I thought you were mine”]

It’s not just about volume. Sometimes Nevin and his team are asked to do something that’s never been done before, like in the song “Wait for It” sung by the character Aaron Burr.

Nevin: We had talked about Burr and his relationship to time and how sound might play a part in that.

Nevin: In the top of “Wait for It,” Burr sings [music clip: “Wait for It”] the question was could we repeat the word day and just capture that one word and repeat it. Of course the easy way to do that is to lock the tempo of the song, pre-record the actor singing day, and just tap it out as many times as you want using playback after he says it.

...but Alex Lacamoire, who wrote the orchestration and did the music direction for Hamilton, didn’t want to pre-record the actor singing. This is because every live performance is different. Different audiences, their reactions, different actors, or sometimes different individual interpretations. Capturing this word from the live performance gives the actor the freedom to interpret the piece that night. So, Lacamoire asked Nevin to capture the single word, “Day,” and do that live during every performance… something that hadn’t been done before.

[Music clip: “Wait for It”]

Nevin: With the help of my extremely talented and very creative game audio engineer Justin Rathman, who continues to mix the show on Broadway, we tried to sort out a way to grab just that one word and send it to an electronic delay and feed it back into the system at just the right moment so that we could capture that word and a few others in that song.

Nevin: One of the things we discovered was that we could do it live.

[Music clip: Wait for It]

[“Theodosia writes me a letter every day”]

Nevin: Once we knew we could do it, then it became an idea. It comes back in the coda of “We Know” in which Burr says...

[Music clip: We Know]

[“We both know what we know”]

Nevin: This reinforces the idea that this character has a very special relationship to time.

Every second of Hamilton has been designed to pull you into the story… and, all of Nevin’s skills were put to the test in the show’s climax, where Hamilton and Burr finally duel.

I should warn you though that we’re about to spoil the end of this duel, but if you paid attention in history class, you should already know this.

[Music clip: 10 Duel Commandments]

[“One, two, three, four

Five, six, seven, eight, nine…

It’s the Ten Duel Commandments”]

Nevin: Lin cleverly puts a duel early in act one so that the audience can understand both the rules of duels which are explicitly told in the lyric of the song, in the lyric of the song, but also the style in which we're gonna present them so that later when we encounter it, we're already familiar with how the duel is gonna work.

Nevin: From a sound point of view, we do the same thing. We sort of set up the duel early in act one with what I like to call a vanilla gunshot which is when Lawrence shoots Lee.

[Music clip: 10 Duel Commandments]

[SFX: Vanilla Gunshot]

Nevin: That gunfire is pretty generic. It's sort of unremarkable that's intentional.

Nevin: One thing to know about that final duel, the final gunshot is rather shocking both in its volume and scale and its kind of complexity.

[SFX: Final Gunshot]

Nevin: The lead up to it, I mean, really, all credit to the music department in terms of the way it's written.

[Music clip: The World Was Wide Enough]

[“One two three four

Five six seven eight nine—

There are ten things you need to know”]

Nevin: The swells and the tic toc sound and the bells, all of that is actually part of the orchestration and brilliantly orchestrated by Alex Lacamoire. There were two other important participants, Scott Wassermann who is, our electronic music programmer and Will Wells who is an electronic music producer, these guys were responsible for crafting the samples you hear in that score.

[Music clip: The World Was Wide Enough]

[“They won’t teach you this in your classes

But look it up, Hamilton was wearing his glasses”]

Nevin: A lot of what you're hearing is just coming straight out what the band is doing and as we lead up to the final encounter between Burr and Hamilton and Burr goes to fire his gun and we stop time.

[Music clip: The World Was Wide Enought]

[“One two three four five six seven eight nine

Number ten paces! Fire!—

SFX GUNSHOT”]

Nevin: The gunshot is actually reversed and choked so that we get the sense that we've stopped that bullet and all the staging supports that idea.

Nevin: We see the characters freeze, we see one of our ensemble members who is actually referred to as the bullet, sort of pinch the air as though she's slowed the bullet down as it crosses the stage and is heading towards Hamilton. The ensemble dances the path of the bullet as Hamilton begins his final soliloquy which is one of the only moments of the show that there is no music.

[Music clip: The World Was Wide Enough]

[“I imagine death so much it feels like a memory...”]

[“...No beat, no melody”]

Nevin: The only sound here is the sound of wind which again has been produced from the orchestration and we take that sound and actually bring it into the room as Hamilton turns and talks, basically as he sees his life flash before his eyes.

[Music clip: The World Was Wide Enough]

[“My love, take your time

I’ll see you on the other side”]

Nevin: When we release time, we repeat the last phrase. He aims his pistol at the sky where he yells, "Wait," and then we have the final gunshot which reverberates through the theater.

[SFX: Hamilton yells, “Wait!” and then Final Gunshot]

[Music clip: “History Has Its Eyes on You INSTRUMENTAL”]

Nevin’s work on Hamilton is a massive labor of love. He continues to work on the show as it premieres in new cities all over the world. Back on Broadway, he’s left an incredible team in place to run the show every night along with some incredible musicians. We’ll hear from a few of them, in a minute.

[music out]

MIDROLL

[Music clip: The Room Where It Happens]

[“I wanna be in

The room where it happens

The room where it happens

I wanna be in

The room where it happens

The room where it happens”]

So, what’s it like to do audio for Hamilton live? To be in the room where it happens?

Anna-Lee: No show is the same every night because there's a different crowd, they're responding differently, the energy is different.

That’s Anna-Lee Craig, Nevin hired her to work on Broadway’s Hamilton as the A2, also known as deck audio.

Anna-Lee: Deck audio is whoever is backstage supporting the audio team while the show is going on. I mic the actors, I make sure that the band is helped. I make sure that the system is working.

A typical day for her is pretty busy.

[Music clip: “Non-Stop”]

Anna-Lee: We come in an hour and a half before the show starts. The first thing we do is turn on the system, make sure everything boots the way that we expect it to.

Anna-Lee: I'm going through each one of the mics and checking the rigging, checking the connectors, checking any custom-fit parts making sure they're clean and making sure that they sound consistent with how we expect them to sound based on whatever mic that is.

<span data-preserve-html-node="true" style=“color:rgb(150,57,152)">Anna-Lee: I have 30 wireless transmitters, that's the number of mics like on people, there are probably 70 mics in the pit. While I'm doing all that with the wireless mics, the mixer will also go through the pit and do a mic check on each one of the mics and make sure that they are going through the monitors. We're just like checking all the microphones and then once they're set and once we've done the mic checks, we chill until half hour.

<span data-preserve-html-node="true" style=“color:rgb(150,57,152)">Anna-Lee: We have 10 minutes of downtime just in case there's an emergency.

<span data-preserve-html-node="true" style=“color:rgb(150,57,152)">Anna-Lee: At half hour, we assist the backstage crew, assist mics getting on to actors.

That’s all BEFORE the show. During the show, she’s putting out fires.

Anna-Lee: I run interference.

<span data-preserve-html-node="true" style=“color:rgb(150,57,152)">Anna-Lee: Like a microphone broke on an actor and we need him to have another mic before his next line, but we can't fully take his wig off so I put a halo one him and an extra transmitter in his pocket until the show gives me a long enough break to like put a real new mic on him.

<span data-preserve-html-node="true" style=“color:rgb(150,57,152)">Anna-Lee: A halo is an elastic loop that is tied to a microphone and you just put it on your head like a headband and then you get like perfect placement. It doesn't look as nice as like our custom-built mics but in a pinch like it will do the job.

[music out]

Justin Rathbun usually mixes Hamilton on Broadway. On his days off Anna-Lee takes the reigns and mixes the show, a job just as busy as being an A2.

Anna-Lee: The way that we mix the show, it's a line by line style. There's not more than one mic open unless everyone is actually singing. Hamilton, Burr, Hamilton, Burr, Hamilton, Burr, Angelica, Hamilton, Burr. It's just one mic open one at a time so that you just have a very clean direct sound and you're not being distracted by any other noise going into our mics.

Mixing audio line by line means Anna-Lee has to be locked into the show for every second of the performance. She’s constantly moving.

Anna-Lee: I'm controlling the band and the reverb with my right hand and the vocals with my left hand and sometimes I'm controlling them all with all 10 fingers. There's not any downtime. I couldn't go to the bathroom, it's impossible.

[Music clip: “Aaron Burr, Sir”]

For Anna-Lee, being that busy and focused on the show is one of her favorite parts of the job. One of her favorite songs to mix is “My Shot.”

Anna-Lee:"My Shot" is like the introduction of Hamilton and also the spot where he decides that he's going to put himself out there and he meets these guys in a tavern.

[Music clip: “Aaron Burr, Sir”]

[“I’m John Laurens in the place to be!

Two pints o’ Sam Adams, but I’m workin’ on three, uh!”]

Anna-Lee: You have to start like again relationship building. It's first just like four guys and they're beating on the table, they're table-rapping. That should feel like it's coming from the stage, but as Hamilton starts to proclaim his like manifesto or like he's going to do great things, the sound starts to expand with him and it gets louder.

[Music clip: “Aaron Burr, Sir” right into “My Shot”]

[“If you stand for nothing, Burr, what’ll you fall for?...”

“Ooh

Who you?

Who you?

Who are you?

Ooh, who is this kid? What’s he gonna do?

I am not throwing away my shot!

I am not throwing away my shot!

Hey yo, I’m just like my country

I’m young, scrappy and hungry

And I’m not throwing away my shot!”]

<span data-preserve-html-node="true" style=“color:rgb(150,57,152)">Anna-Lee: Then Lauren says, let's get this guy in front of a crowd. Then the ensemble comes in. The level, the dynamic level takes a step up.

[Music clip: “My Shot”]

[“Let’s get this guy in front of a crowd

I am not throwing away my shot

I am not throwing away my shot

Hey yo, I’m just like my country

I’m young, scrappy and hungry

And I’m not throwing away my shot”]

Anna-Lee: We don't go all the way yet because we've got another journey to go on. Then the town's people get added in and they're running through the streets. Laurens is saying, whoa. He's telling everybody else to like jump in, then we add like some reverb in and it's all through the town.

[Music clip: “My Shot”]

[“Ev’rybody sing:

Whoa, whoa, whoa

Hey!

Whoa!

Wooh!!

Whoa!

Come on, come lets go!”]

Anna-Lee: You can hear the sound surrounding you in the audience because the reverb is in surround. Llike you're a part of it. Then we suck back down into just like Hamilton's monologue.

[Music clip: “My Shot”]

[“I imagine death so much it feels more like a memory

When’s it gonna get me?

In my sleep? Seven feet ahead of me?”]

Anna-Lee: When he finally starts talking to a crowd again and it builds to the fullest height and then we like go through the whole final chorus. Everybody who's in the show is singing and I am not throwing away "My Shot."

[Music clip: “My Shot”]

[“And I am not throwing away my shot

I am not throwing away my shot

Hey yo, I’m just like my country

I’m young, scrappy and hungry

And I’m not throwing away my shot”]

Anna-Lee: You're like living that huge, loud, big moment for the rest of the song and then we like slam it for the button.

[Music clip: “My Shot”]

[“Not throwin’ away my—

Not throwin’ away my shot!”]

For Anna-Lee, mixing the show live is about staying true to Nevin’s soundscape, but it’s also about feeling out actors and the audience during every performance.

Anna-Lee: You're also building with the actor's intensity. He's starting to like believe that everyone is onboard.

Anna-Lee: As you feel like you're like winning people over that are in the cast, you're also winning over the audience and the audience can take more decibels. If they're not won over yet you have to slowly build, sometimes if you feel like the crowd is not quite ready for that loud level yet you can hear people start to rustle and you can almost feel people want to get up out of their seats. Once you reach that kind of fever pitch feel, that you can really just go for it.

We can’t have an entire episode about sound in a musical like Hamilton without talking to one of the musicians.

Benny: My name is Benny Reiner and I play percussion.

Benny is part of Hamilton’s Grammy-winning orchestra. When he says he plays percussion, you might be thinking he sits behind a few drums and obscure instruments, but his job entails so much more than that.

Benny: My setup consist of different weird things. I have a MOTIF keyboard which is an electric piano basically. I play little patches like vibraphone [SFX], I have a sampler that I basically play anything that would be from a drum machine [SFX] or a sample.

Benny: Then there's also what you just think of percussion, just tambourine [SFX], shakers [SFX], concert bass drum [SFX], random stuff like that.

That’s not all Benny does. Another big part of his job is running a piece of software called Ableton.

Benny: The fundamental function of it would be precise timekeeping. Most of the show is in the vain of hip hop and RNB and pop and a lot of contemporary elements. Since there is so much of that in Hamilton, the role of the metronome is to really keep that time together.

Benny: As a human, we don't have perfect time, no show is the same because everything we do has variance in it.

The audience and actors on stage never hear the click track. It’s just for the orchestra to keep time. This is what the audience hears this…

[Music clip: “What’d I Miss”]

[“There’s a letter on my desk from the President

Haven’t even put my bag down yet

Sally be a lamb, darlin’, won’tcha open it?

It says the President’s assembling a cabinet...”]

And this is what the musicians in the orchestra hear…

[Music clip: “What’d I Miss” with added 178 BPM metronome]

[“There’s a letter on my desk from the President

Haven’t even put my bags down yet

Sally be a lamb, darlin’, won’tcha open it?

It says the President’s assembling a cabinet...”]

Ableton keeping time for the pit is important, but it has other functions as well.

Benny: There are certain track elements, stuff that really is impossible to play live. Stuff that's going through phasers or effects or there's information that gets sent from it to control certain lighting things.

Controlling lighting cues through the same software that keeps the orchestra in time means that vocals, orchestra, choreography, and lights will all sync perfectly. That’s an important part in creating Hamilton’s moments of sensory immersion.

While Benny has a lot of technical responsibility, when it comes down to it, he’s a musician at heart. You can tell that from the way he talks about his favorite song to perform, the love song “Helpless.”

[Music clip: Helpless]

[“Ohh, I do I do I do I

Dooo! Hey!

Ohh, I do I do I do I

Dooo! Boy you got me helpless”]

Benny: I love "Helpless" just because it just feels great. You're in there, you're playing, you're just making things feel good essentially and that's one of my favorite things about music is just making people feel happy and making people feel warm.

[Music clip continues]

[music out]

[Music clip: “Quiet Uptown Instrumental”]

Anna-Lee: Our main job is serving the story and the narrative.

Anna-Lee: When I'm mixing, I'm really a part of the show like an intimate, intricate cog in what makes Hamilton work. I know that everything that I do is very directly affecting the 1300 people watching the show.

Anna-Lee: I’m also an extrovert and a people person I get to be backstage. I make really strong friendships with actors and crew members and musicians.

Benny: The ultimate reason why I love doing what I do is the ability to connect with people.

Benny: You got to really bring it if you want to really connect and relate to somebody. That's really fulfilling to me. It’s like, if you put enough of yourself into something honestly and have that reciprocate, somebody listen to it or witness it and really have them feel something, that's it for me.

Nevin: In some ways, Hamilton is one of the hardest things I've ever worked on and in other ways, it was also one of the easiest things I've ever done because it is so well written and so beautiful directed and staged and orchestrated that my job was simply to respond to it in a credible and exacting way.

Nevin: This extends to everyone who worked on it. I mean Howell Binkley's lighting is exquisite and sharp and just so focused and Paul Tazewell's costumes tell the story so beautifully and so subtly throughout the play. It's extraordinary.

Nevin: The set moves in such a way and gives you a background in such a way that you're never unsure about how you're going to encounter these characters and the story.

Nevin: I love the people. They're some of the smartest people I know, in any field. I love the banter. I love the fact that part of my job is having conversations, laughing, making things, criticizing things, and striving to make things better all the time. I love the knowledge that an audience really has no idea what it is that I've done or even what we've done as a team to get them to feel a certain way or get them to look in a certain direction or get them to experience a moment in the way we've crafted it because we've done our job so quietly.

Nevin: I love that. I like the theater. I like going to the theater. I like plays and musicals, so that I get to do this for a living is pretty exciting for me.

[music out] [Music clip: “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story”]

CREDITS

Twenty Thousand Hertz is hosted by me, Dallas Taylor and produced out of the studios of Defacto Sound. A sound design team dedicated to making television, film, and games sound incredible. Find out more at defactosound.com.

This episode was written and produced by James Introcaso… and me, Dallas Taylor. With help from Sam Schneble. It was edited, sound designed and mixed by Colin DeVarney.

Thanks to our guests Nevin Steinberg, Anna-Lee Craig, Benny Reiner, and Abe Jacob. Thanks also to the producers of Hamilton for their immense help with this episode. If you’re interested in seeing Hamilton, which I highly recommend, you can do that right now on Disney Plus. And I would love to hear your thoughts on Hamilton. You can tell me on Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, or by writing hi@20k.org.

Finally, we need your help to spread the word about Twenty Thousand Hertz. So tell your family members, tell your friends, tell your kids, tell your grandparents, tell everybody! If you have to show them how to subscribe to a podcast, we would be honored if we were their first subscription.

Thanks for listening.

[music out]